October 13, 2024.

Happy Halloween! (It’s basically Halloween, right?) Since we’re officially in spooky season, it’s only right that I analyze a horror game that was absolutely formative to my tweenage self— Five Nights at Freddy’s. Or, well, at least content about it. Despite my love of horror novels (I just finished We Came to Welcome You by Vincent Tirado), I’m a giant baby who can’t play horror games— so take this analysis with a grain of salt, because I’m working off of transcripts and gameplay breakdowns for this one.

If you’re used to Game Theory-style FNaF analysis, this is going to be a little different. Don’t expect any major lore analysis here, or claims about a single “true” story, or even a series timeline. I’m only looking at the first game, and I’m treating it like a standalone title (you could not pay me to try to understand the FNaF timeline). I’m also analyzing the gameplay more than the story, in all honesty. Take this article as a potential alternate reading of the original Five Nights at Freddy’s; not a counterargument, not a grand new theory, just some Halloween-season fun.

CONTENT WARNING: A brief and vague, but important, discussion of child murder and general violence. It’s a horror game, after all! Also, some GIFs in this post contain flashing lights and/or glitch effects.

About Five Nights at Freddy's

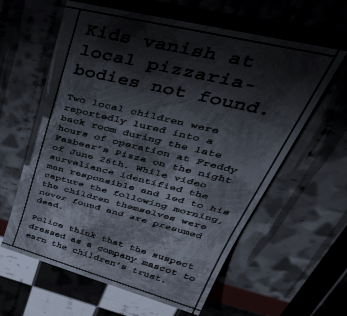

Five Nights at Freddy’s is a horror game developed by Scott Cawthon and released in 2014. The player takes the role of Mike Schmidt, a security guard in a Chuck-E-Cheese-like children’s entertainment establishment; Mike’s job is to monitor the high-tech, free-roaming animatronics during the night. But as we learn from the previous guard (known to fans as Phone Guy), these animatronics believe that the guards are endoskeletons and try to stuff them in animal suits, killing them in the process. To keep Mike (themself) safe, the player must keep track of the animatronics’ movements using the building’s security cameras, then close the doors when they get close— all of which uses up precious, limited power. It is also heavily implied that five children were murdered on the premises and hidden inside the animatronics; though heavily elaborated on later in the series, in the first game, this plot is only made known through newspaper articles semi-hidden in certain security camera shots.

Surveillance as the Core Gameplay

Here’s the world’s shortest and most reductive horror game design crash course:

- You need a threat, or it wouldn’t be horror.

- You need a defense against that threat, or you couldn’t win the game.

- You need a limit to that defense, or why have a threat in the first place?

The threat in FNaF is, obviously, the animatronics trying to shove you in a bear suit. The defense and its limits are the interesting parts. While the doors to the office may seem like the obvious “defense”— and they are!— your very first line of defense is the security camera monitor (Tech Rules, 2020, 0:52), since that’s what tells you when to use those doors (ibid., 5:05; Kizzycocoa, n.d.-b). In his book chapter “Insecurity as an engineering problem: The technosecurity network,” criminology professor Stéphane Leman-Langois writes that security cameras “are universally seen as effective risk reduction devices” (2013, p. 87). This is because they embody the idea that surveillance overall is effective as such— which we believe to such an extent that we often (mistakenly) use the two words interchangeably (ibid., p. 78). By making security (surveillance?) cameras the player’s first line of defense against a dangerous threat, these cultural/political/what-have-you views of surveillance and security are baked into the gameplay itself.

And then there are, of course, the limits. There are two key limits to the power of the surveillance cameras in FNaF; one is the limited battery power, which prevents the player from perpetually staring at the camera feeds (Kizzycocoa, n.d.-b). The other, in tension with that, is the need to constantly pay attention to those cameras (when they are open), splitting your mental bandwidth across four different threats with (somewhat) different movement patterns (Tech Rules, 2020) and several disjointed, static-camera-angle rooms. Leman-Langois notes that security cameras “are obviously flawed because security matters continue to preoccupy even after state-of-the-art networks are installed” (2013, p. 87), but these flaws are attributed to technological limitations or human error, not surveillance itself (ibid., pp. 87-88); as he puts it, “under-surveillance is taken as the cause of increased risk” (ibid., p. 88). In fact, his example of a camera network that makes an easy-to-navigate 3D model of the space (ibid.) is a real-world solution (?) to the disjointed-camera-angle challenge present in FNaF— and while Leman-Langois doesn’t discuss battery life, the “unsatisfactory low light performance, resolution, [and] lens power” they use as examples of tech issues (ibid., p. 87) are important aesthetic components of the horror in this game (see Tech Rules, 2020, 0:30). The explanations surveillance-as-security gives for surveillance’s failures are transformed into the very challenge that makes FNaF fun to play.

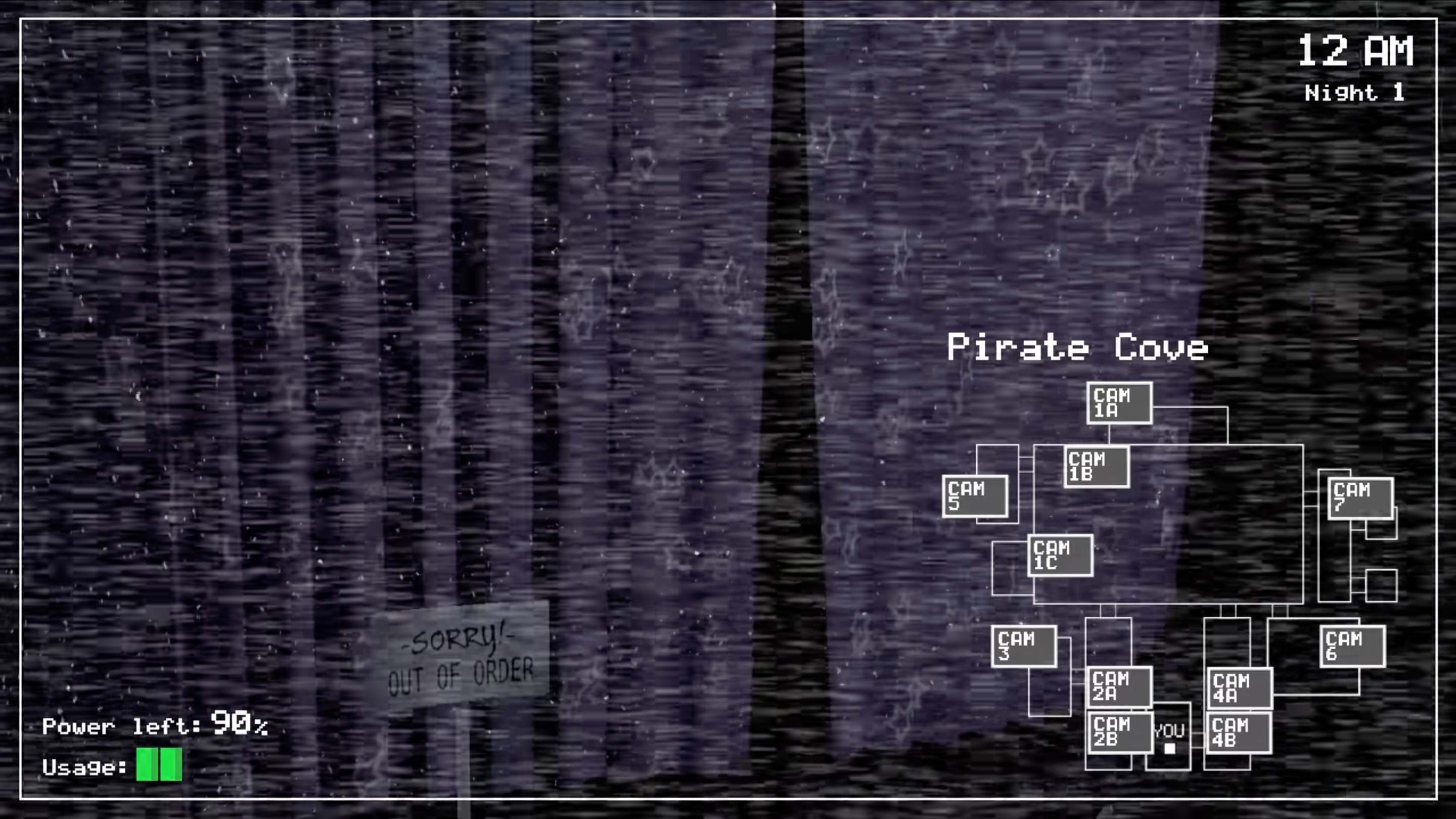

Left: The player rapidly looks through the security camera footage; note how even adjacent rooms feel disconnected (SHN Survival Horror Network, 2021, 1:34, sped up). Right: The power runs out in the security office, leaving the player vulnerable to Freddy's attack (SHN Survival Horror Network, 2021, 36:37).

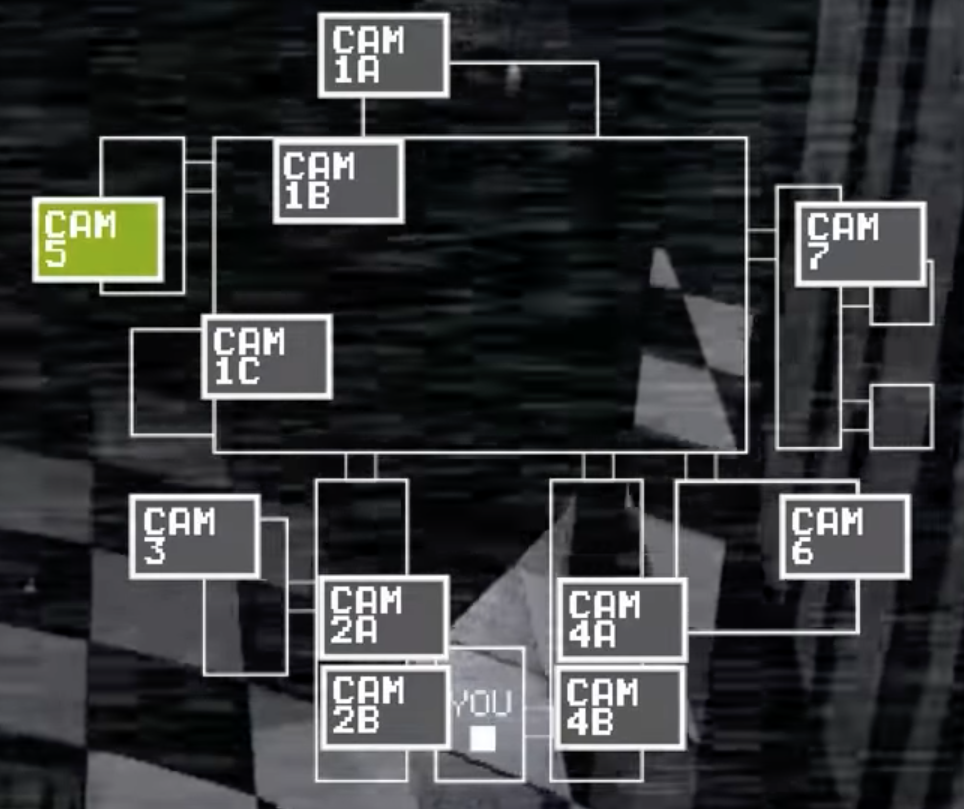

Because we play as the security guard, we are positioned to put ourselves in his shoes; the animatronics are dangerous killers, and the cameras and doors are how you keep yourself safe. But let’s take a step back and look at the shape of the surveillance here.

- We have a single watcher. He is significantly outnumbered by those he watches.

- He watches from a stationary position. None he watches may enter this room.

- He is able to see into any room in the building at any time. Though he can only see into one at once, there’s (mostly) no way for others to know where he’s looking.

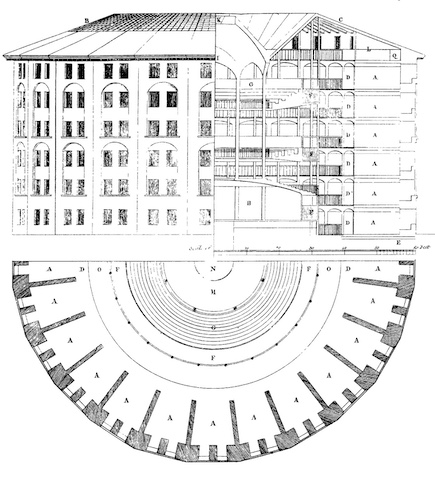

Bestie, that’s the panopticon (Foucault, 1975/1995, pp. 200-201). If we step out of the guard’s shoes and into the animatronics’ suits (without dying in the process), Five Nights at Freddy’s looks a lot less like a horror game and a lot more like a prison break.

Or at least it would if the motives lined up.

Left: A map of the pizzeria; note that you can select any camera to view at will (SHN Survival Horror Network, 2021, 5:14). Right: A technical schematic of the layout of the Panopticon; note that the guard in the central tower can see into any cell at any time (Revely, 1791).

The Rational Man(imatronics)

I know, I know. I talked about the assumption of humankind as rational in last month’s article about SpongeBob SquarePants. But the ideology of surveillance-as-security hinges on the idea that crime happens because people, assumedly rational, do a risk-benefit analysis of committing crimes, then decide that the benefit of committing crimes outweighs the risk of getting caught and/or the punishment they would incur if so. Increasing surveillance increases that risk, meaning more people will decide against committing crimes. Anyone who so irrationally chooses to commit crimes in the face of such high risk is punished and removed from society in one fell penal swoop— “those incorrigibles who cannot ‘learn’ to choose their path more wisely must be perpetually taken out of circulation” (Leman-Langois, 2013, p. 79). (This ideology ignores so many other factors of crime that it’s practically useless, yet we base so much of our “justice” system on it…)

Which brings us to the animatronics. The reason why the animatronics are a threat, plot-wise, is that they mistakenly believe that you are an endoskeleton that must be returned to its suit (Kizzycocoa, n.d.-b). In other words, their behavior is dictated both diegetically (ibid.) and extradiegetically (Tech Rules, 2020) by computer programs— and what is more rational, more of a strict conversion of mathematical calculation to behavior, than a computer program? And the fact that they are specifically malfunctioning, i.e. acting against the “rational” behavior that “should” be hard-wired into them, fits neatly with Leman-Langois’ description of criminality as viewed by surveillance-as-security ideology, even down to the wording of “taken out of circulation” (2013, p. 79).

The behaviors of the animatronics in turn mirror the expected/desired ways surveillance increases security; “…to punish, ‘scare straight’, to deter; and if that fails, to neutralize” (ibid.). Foxy only moves if the player does not keep checking back on him (Tech Rules, 4:26), fitting with the idea that the risk of being caught that surveillance brings would deter people from acting out of line. Freddy, Bonnie, and Chica, meanwhile, pursue the player no matter what (ibid., 4:19), but when you see them disappear from the cameras, you know to close your office doors, neutralizing the threat. (Okay, technically the others don’t move while you’re actively watching them either, but in terms of how they react to your camera usage, this basically covers it; ibid.). All in all, just like how the role of security cameras in surveillance-as-security ideology is baked into FNaF’s gameplay, the characterization of the animatronics works as a metaphor (if loosely) for the rational-man understanding of criminality.

Left: Foxy's hiding in Pirate Cove, waiting until he isn't watched to come out (SHN Survival Horror Network, 2021, 6:23). Right: After seeing Bonnie disappear from the show stage, the player checks the hallway. Upon seeing Bonnie right outside their window, they hurriedly close the door (SHN Survival Horror Network, 2021, 11:10).

Stuck in the Surveillance Box

But here’s the thing; if the animatronics can mistake you for an endoskeleton, that means they must, in some way or another, be able to see you. And being animatronics, it’s not like they have real, fleshy eyeballs; they are essentially fuzzy robots, and so they must “see” you with cameras. This means that the animatronics, despite being the stand-in for criminals in this reading, are also somewhat of a surveillance camera system themselves. An extremely technologically advanced surveillance system, in fact— so advanced that the innovations start to hinder themselves and harm others. They have to roam around to keep their “servos” from “locking up”, something they wouldn’t have to do if they were stationary like Mr. Charles Entertainment Cheese; they wouldn’t mistake you for an endoskeleton if they didn’t have those probably-useless cameras in them in the first place.

One may be tempted to read this as a commentary on the uselessness of surveillance camera innovation. After all, when discussing how security can’t seem to think outside of the surveillance box, Leman-Langois writes that “evolutions and innovations are determined by the nature and function of existing devices” (2013, p. 88, emphasis in original); the animatronics are a case where refusing to discard surveillance in favor of extremely advanced bandaid fixes has literally deadly consequences. But considering how heavily surveillance-as-security ideology is baked into the gameplay, I have a hard time taking this reading seriously. Instead, I think this is better seen as an example of just how much we take surveillance-as-security as a given. When trying to come up with an in-universe explanation/justification for why the animatronics act they way they do, Cawthon immediately reached towards a surveillance system gone wrong, not because of the surveillance itself, but because of tech issues.

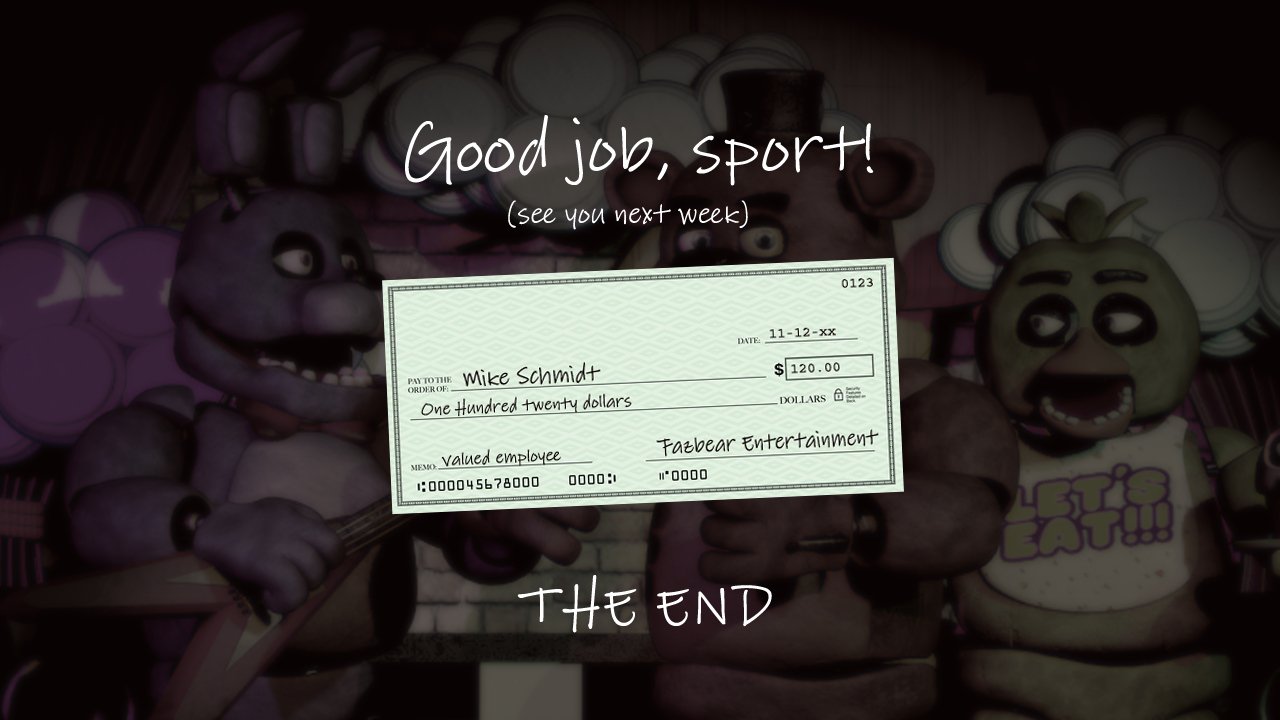

The screen you see when you beat FNaF (Kizzycocoa, n.d.-a). Alternatively, the easy paycheck and happy animatronic band the FNaF world would have if their malfunctioning cameras didn't make them try to kill you.

And since we’ve mentioned the author now, I have to address the elephant in the room; Scott Cawthon, politically speaking, sucks. He sucks in a way that is actively hurtful, harmful even, towards (ironically) a large portion of his fanbase— and towards me. So why am I writing about his work? Or, on the other end of the spectrum, why am I writing about him? While I generally avoid acknowledging the author if at all possible (not because it’s a good approach to media analysis, but because it’s a fun one), I think it’s important to mention here because, well… surveillance-as-security itself, while being widely accepted, is also deeply conservative. Or, rather, the attitude towards criminals and criminality from which it stems— the idea that crime is an issue of individual decision-making and risk-benefit analysis, with zero acknowledgement of systemic factors (Leman-Langois, 2013, p. 79)— is deeply conservative. I’m not saying necessarily that Cawthon’s conservative beliefs themselves influenced his game design decisions.

I have no evidence to support that, and it steers too close to trying to determine authorial intent (or, worse, subconscious thought) for my liking. What I find more interesting is the parallel between Cawthon and surveillance-as-security themselves, in the way that nobody expects/ed their conservativism; the revelation of his political donations hit the fandom like a truck, in the same way that page 79 of Leman-Langois hit me. If anything, I see this as a call to dig deeper the media we consume— especially that which we feel we aren’t “supposed” to— to uncover what ideology we might be absorbing and/or taking for granted within it. And isn’t that what this blog is about?

Oh Right, the Child Murder

Though the whole thinking-you’re-an-endoskeleton thing is the stated reason behind why the animatronics are trying to kill you, it’s not the whole story. In fact, given that Phone Guy seems to not know much about the animatronics’ tech (“something about their servos locking up” isn’t exactly reassuring phrasing; Kizzycocoa, n.d.-b), who knows if that stated reason is even right? Perhaps it’s time to bring in the other side of the story– those freaky newspaper clippings. The obvious story they tell is, of course, that bunch of kids were murdered at the pizzeria and their bodies were hidden in the animatronic suits. Given that the bodies were never found (Kizzycocoa, n.d.-a), the implication is clearly that the kids’ bodies are still inside the animatronics, even as they hunt you down.

Leman-Langois writes that “prevention-oriented technologies—” surveillance systems included— “do not solve future problems, only future reoccurrences of past problems” (2013, p. 90), i.e. they are “reactive security” (ibid., p. 80). Anyone who’s flown on an airplane this millennium has experienced this when asked to take off their shoes, as that rule was made in response to a bomb hidden in a shoe (ibid.). In a way, one could think of this phenomenon as previous attacks haunting our present-day security measures; the continual performance of these measures is an implicit (and not necessarily correct) affirmation that if we do not take these security measures, the problem will come back. If we do not take off our shoes, someone else will sneak a bomb into theirs. If you stop watching the cameras, your dead body’s getting stuffed in the bear suit.

On that note: there’s a quote from the first of the newspaper clippings that really stood out to me. It reads as follows:

One of the newspaper clippings visible in FNaF (Kizzycocoa, n.d.-a).

While video surveliance [sic] identified the man responsible and led to his capture the following morning, the children themselves were never found and are presumed dead. (Kizzycocoa, n.d.-a)

Surveillance may make it easier to catch criminals, but that doesn’t necessarily keep us safe.

Conclusion

This is another article where I have to shout out one of my old professors, this time Dr. Russ Newman. I first read these works by Leman-Langois and Foucault in his class— in fact, I thought of this reading of Five Nights at Freddy’s while reading the former for homework. Prof. Newman, if you’re reading this, sorry that I’m using your assigned reading for… this.

My next post will be on-time, I promise. Save the date for 11/3 and flame me online if I miss it. Get ready for my weirdest article yet. :)

References

- Cawthon, S. (2014). Five Nights at Freddy’s [Video game]. ScottGames. Cited only indirectly through other sources, but important to include nonetheless.

- Foucault, M. (1995). Discipline and Punish (A. Sheridan, Trans.; Second Vintage Books Edition). Random House. Original work published 1975.

- Kizzycocoa. (n.d.-a). FNaF 1 Newspapers and Clippings. Fnaflore.com. Retrieved October 10, 2024 from https://fnaflore.com/resources/newspapers-and-clippings/fnaf1/

- Kizzycocoa. (n.d.-a). FNaF 1 Phone Transcripts. Fnaflore.com. Retrieved October 10, 2024 from https://fnaflore.com/resources/audio-transcripts/fnaf1/

- Leman-Langois, S. (2013). Insecurity as an engineering problem: The technosecurity network. In K. Ball & L. Snider (Eds.), The Surveillance-Industrial Complex: A political economy of surveillance (pp. 78–92). Routledge.

- Tech Rules. (2020, January 16). Ruining FNaF by Dissecting the Animatronics' AI | Tech Rules. YouTube.

Image-Only Sources

- Reveley, W. (1791). Plan of Jeremy Bentham’s panopticon [Technical diagram]. Wikipedia (Public Domain). Retrieved October 11, 2024 from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Panopticon#/media/File:Panopticon.jpg

- SHN Survival Horror Network. (2021, December 5). Five Nights at Freddys | 4K/60fps | Longplay Walkthrough Gameplay No Commentary. YouTube.

Cite This Article (APA)

Miller, A. (2024, October 13). Five Nights at Freddy's - Surveillance as Security as Gameplay. Grab a Shovel. https://primmsfairytale.neocities.org/blog/2024-10-13-Five-Nights-at-Freddys